21st Century Tranist

I write to help me learn and grow as a professional, demonstrate my knowledge, flesh out and organize my ideas, and enjoy a free and flexible outlet.

All articles are posted here on this website. Some articles I keep more private and are exclusively posted here, some are also posted on my Substack account.

Modernizing travel between Missouri's two largest cities

From incremental improvements to building an entire new high-speed line, I explore the possibilities to improve rail service between St. Louis and Kansas City based on past plans and research.

Missouri is one of the handful of American states that has two major cities with large metro areas. Yet, travel between them has hardly changed in the last few decades.

Because the best Missouri and Amtrak can do is a 5.5-hour train ride, most by default just do the 3.5- to 4-hour drive on Interstate 70 or go through the entire painstaking airport experience for an hour-long flight.

But there was a time when the State of Missouri had ambitious goals for modern train service between its two major cities. Through various reports and proposals, the Midwest Regional Rail Initiative (MWRRI) and the Missouri Department of Transportation (MoDOT) laid out a transformative vision for much faster and more frequent trains than the state and Amtrak operate today.

Had those plans been implemented, traveling across the state would be faster, safer, more comfortable, and more environmentally friendly than it is today.

Image 1: A Siemens SC-44 Charger pulling an eastbound Missouri River Runner service stopping at Kirkwood Station. (Source: me)

Unlocking the Missouri River Runner’s full potential

The Missouri River Runner is Amtrak’s state-supported route between St. Louis in Kansas City, with 8 stops in between. This twice-daily service is the present-day consolidation of Amtrak’s old cross-state routes: the Ann Rutledge and Missouri Mules, which were merged together in 2009.

As for actual changes to the service itself, unfortunately, not much has changed over the years.

When I was a little kid, my family and I would travel to Kansas City around the holidays every year on Amtrak. In the early 2000s, the train averaged 50-60 miles per hour, topping out at just over 70 mph with a scheduled runtime of 5 hours and 50 minutes. Today, the average and top speeds are the same, and the scheduled runtime is barely faster at 5 hours and 40 minutes.

The only large improvement in recent years was the construction of a 9,000-foot passing loop near California, Missouri in late 2009. It was successful, as ridership grew, but the goal of the project was to reduce conflicts with freight trains to improve on-time performance. Make no mistake, this was not to achieve higher speeds and reduce runtimes, but simply to make sure trains actually ran on time. This is the only “upgrade” that has been made between the last time I rode the train when I was 5 or 6 years old to when I took it for the first time in almost two decades in December 2024.

Image 2: Existing Missouri River Runner route. (Source: jkan997 - http://sharemap.org/public/Amtrak_Missouri_River_RunnerGeospatial data sources: Open Street Map Data (ODbL) - http://www.openstreetmap.org/copyrightNORTAD - http://www.bts.gov/publications/north_american_transportation_atlas_data/Natural Earth - http://www.naturalearthdata.com/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29259405)

From the late 1990s to the early 2010s, the MWRRI and MoDOT had plans for significant service improvements through incremental upgrades to infrastructure. They wanted to enable top speeds of at least 90 miles per hour, with hopes of eventually exploring the feasbility of 125 mph and slashing runtimes to under four hours. They also wanted to start running six or more round-trip trains a day.

The goals outlined by the MWRRI and MoDOT were not just arbitrarily stated; they were actual studied solutions to increasing train speeds.

Double-tracking

A PE/NEPA application in March 2011 laid out plans to connect existing sidings that together would form a second mainline track on the Union Pacific Sedalia subdivision, which is between Pleasant Hill, MO, and Jefferson City, MO. This would’ve eliminated bottlenecks to allow Amtrak trains to reach and maintain speeds of at least 90 miles per hour, but the segment is still mostly single-tracked today.

Tilting trains

Even with eliminating freight bottlenecks, the route’s curves limit how fast trains can go. In a 2004 report, the MWRRI stated that tilting trains could safely reach speeds up to 90 miles per hour on most of the route’s many curves and help reduce runtimes to 4 hours and 42 minutes.

Grade-crossing improvements

MoDOT identified at-grade crossings that needed new lights and gates and wanted to explore the feasibility of sealing several of them off completely. These measures would not only improve safety, but allow higher speed limits through those areas.

Getting runtimes to under 5 hours is possible and would be a significant improvement, but this specific corridor has its limits. Even if conflicts with freight trains could be eliminated, there are too many curves, and much of the terrain in central Missouri is very hilly.

Image 4: A Missouri River Runner train at St. Louis Gateway Station in April 2022. (Source: Bob Johnston, accessed via trains.com)

This corridor is great for a conventional intercity service that connects Missouri’s two major metro areas with its capital in Jefferson City and other great cities all on one line. But true high-speed express service can not be achieved here. For faster trains for travelers going directly between St. Louis and Kansas City, Missouri needs a new right of way that is straighter, flatter, can be electrified, and entirely dedicated to passenger trains.

A real high-speed rail corridor

St. Louis to Kansas City became a federally designated corridor in 2001. Over the next decade, MoDOT tried to acquire funding and implement provisions to identify and evaluate a dedicated high-speed rail corridor with long-term plans for 180 mph speeds and electrification.

Unfortunately, these plans lost momentum when Missouri State Legislators blocked funding for high speed rail, along with the other budget constraints. There is no mention of these projects or initiatives in any MWRRI reports or MoDOT rail plans past 2012.

However, these dormant plans were explored enough to give us a glimpse of what a dedicated route in Missouri would look like.

Building along Interstate 70

For a true, dedicated high-speed rail line between St. Louis and Kansas City, it would likely be built along Interstate 70. Compared to the Missouri River Runner route, I-70 is a pretty straight route, and the terrain throughout is much flatter.

There have been a few mentions of building a new right-of-way along Interstate 70 in past studies.

MoDOT I-70 improvement study

This 2001 report weighed a number of options for alleviating traffic on I-70.

While the “Selected Strategy” was to widen the highway and the consideration of building high-speed rail was discarded, the report suggested that the “extra-wide median” being built could be allocated for a high speed rail line in the future.

MoDOT is committed to the further consideration of this space by a future high-speed rail system, but is currently uncommitted regarding the reservation of this space for the specific purpose of highspeed rail. — MoDOT, 2001

Hyperloop feasibility study

Remember the hype around the Hyperloop? Well, in case you didn’t know, St. Louis to Kansas City was once a favored route.

While the initiative lost momentum because the technology is impractical, a feasbility study shows the viability of building infrastructure along I-70. In the report, I-70 was deemed a strong corridor not only because the right of way already existed, but that it was relatively straight and flat.

“The report confirms viability of the I-70 based route through an exhaustive examination of the social impact, station locations, regulatory issues, route alignments and rights-of-way associated with a new hyperloop system that would connect Kansas City, Columbia and St. Louis.” — Virgin Hyperloop One

NextSTL’s high-speed rail series

NextSTL is a local online source covering a range of urban topics and issues in the STL area. In 2013, it wrote a three-part series about high-speed rail in Missouri.

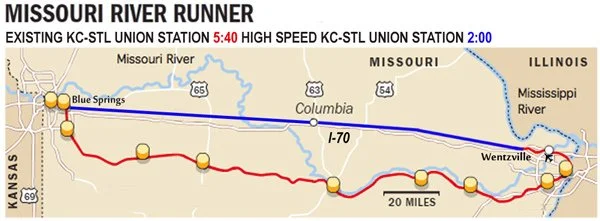

Part I discussed building a new dedicated right-of-way between Wentzville (STL area suburb) and Blue Springs (KC area suburb) along I-70. In those suburbs, the new dedicated high-speed line would connect to existing rail lines that run into city centers (see Image 5).

“By building a dedicated HSR track between Blue Springs and Wentzville, travel time could be slashed to an hour between those two cities and to less than two hours between the downtowns of KC and STL.” — Frank DeGraaf, Contributor, NextSTL

Image 5: Proposed high-speed line along I-70. High-speed line is blue, existing Missouri River Runner and existing railroads are red. (Source: NextSTL)

Electrification is not only a cleaner and more sustainable technology, but electric trains are faster and more reliable. Electrification is an advantage of building rights of way anywhere. As long as Union Pacific owns the existing MRR corridor, it is unlikely to be installed unless new regulations would encourage or incentivize it.

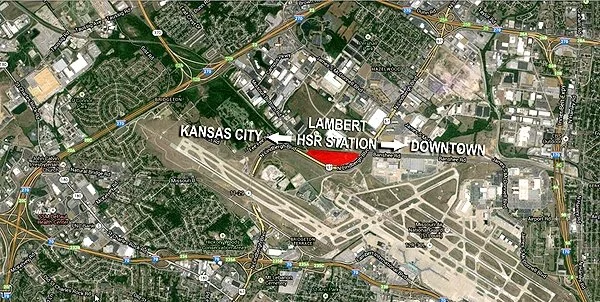

Image 6: Concept high-speed rail station near Lambert Airport, existing rail track rights of way, and Interstate 70 (Source: NextSTL)

Next steps

Missouri has a lot of work to do. If there’s a day the state decides to get serious about modernizing cross-state travel, here are a few first steps:

Missouri River Runner

Revive plans to study and/or secure funding for previously mentioned upgrades— tilting trains, double-tracking, and crossing upgrades.

Increase service frequencies to 10 daily round-trip trains, per the High Speed Rail Alliance’s recommendation.

High-speed rail

MoDOT should form a high-speed rail commission—like the Illinois High Speed Rail Commission—to study ridership, identify and design a corridor, make recommendations for planning a network, and propose a governance structure.